Book Reviews With Jenny Dowell

Jenny is an avid reader and vocal supporter of libraries. Her reviews are always thought-provoking and well constructed. A link to reserve each book appears at the end of her review. You can receive Jenny's reviews and other exciting news every month in our library eNewsletter by subscribing at the following link www.rtrl.nsw.gov.au/subscribe.

July 2025

The Meeting Place

The Meeting Place

by Ruth Rosenhek

This month Jenny's recommendation is The Meeting Place.

Book Description: Amidst a backdrop of drought, pandemic and resource scarcity, an automated robo-guard patrol system tears through the region and rounds up members of the community. Three friends - Gale, Lis and Sara - persevere through separate hardships as their stories of family violence, stolen generation, and gender dysphoria emerge. With Gale in a cell in a quarantine facility, Lis with two children holed up at the edge of town and Sara stuck out on a rural property in isolation while her medications run out, the love the three have for each other shines through. Will they be able to reunite and what will be the cost? With the pulse of a thriller, The Meeting Place is a dystopian place-based novel about ordinary people confronted by extreme circumstances.

June 2025

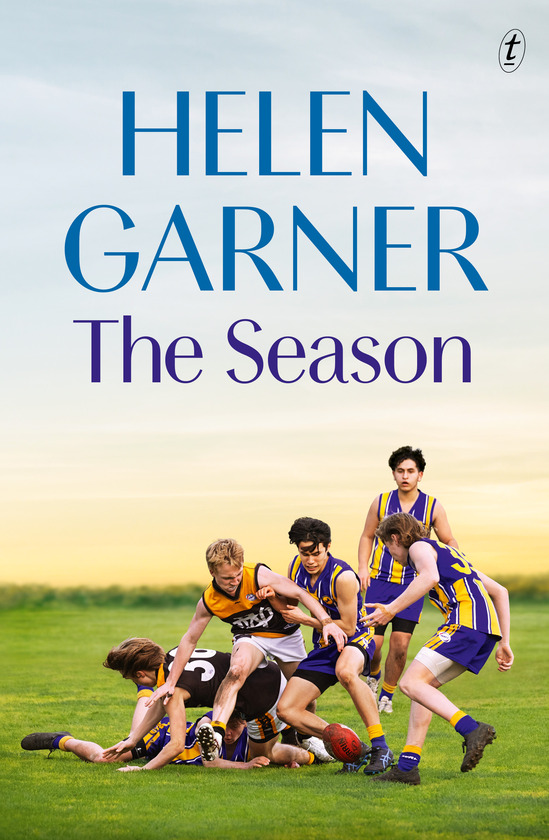

by Helen Garner

This beautiful book is a love song between grandmother and grandson and to the transformative and uniting power of our national game, Aussie Rules football.

For a season in 2023 Garner takes grandson Ambrose to his training nights and games for Flemington Colts U16 team with a chapter for each of the seven months from February to August, from preseason to the finals.

This is more than a ‘sports’ book, it is a non-fiction account of the easy bond between an 80-year-old grandmother and a boy growing into a young man.

Garner and her daughter’s family live side by side in inner suburban Melbourne, with no dividing fence. Abby and Helen move between the two houses with ease as this extended multigenerational family bridges the intergenerational divide easily.

The description of her realisation when she enters his bedroom to see this muscly lanky grandson sprawled on his single bed in his boxers and realises he is no longer a kid, resonates with every parent.

I am an unabashed long time AFL fan (my team is Geelong, the Cats) and so the names in here such as Jezza, Libratore, Blight, Bont etc, are familiar to me, as are the common terms of the game such as torp, tackle, holding, mark, flank, ruck, and even ‘he’s gorn’. As others have told me, it’s not necessary to love or even understand Aussie Rules to love and understand this book. It transcends the game.

The descriptions of dark and cold Melbourne winter nights where Garner is the sole observer of the weekly training sitting on the back of a bench seat, are a slice of suburban life with joggers, dog walkers, and the traffic nearby. These words pictures illustrate Garner’s consummate writing skill. The ordinary is made literary. Garner infuses her writing about her observations with disclosures of her own vulnerability, self-doubt and ageing body with its diminished hearing and eyesight.

Abby’s coach Archie is a gem. He understands his ‘boys’ and they understand what he wants of them, even in his absence. The young men themselves are lovingly described too. There is harshness here also. It’s not all roses. The fear of injury, especially concussion, the interference of aggressive fans ensures there's no sugar coating of this sport.

Garner intersperses her family narrative with stories of her own beloved Western Bulldogs games.

Having lived for the first four decades of my life in Melbourne, I can attest to the all-consuming nature of AFL in the lives of most Victorians. ‘Who do you barrack for?’ is a common conversation starter at any meeting of strangers. Every workplace and family is alive with talk of the game, especially on Fridays and Mondays. Aussie Rules transcends class, schooling, and job, unlike NSW where there is a divide between rugby union and league followers. Whether a judge, unemployed, tradie, student, doctor, teacher, wait staff, or factory worker, EVERYONE can and does talk AFL.

Helen Garner admits to being a recent convert to the game, having lived in Sydney for many years. Her phone wallpaper is an emotion-filled photo of Bulldogs captain Marcus Bontempelli assisting injured Josh Bruce off the ground after a defeat—Garner described it as a Homeric sense of brotherhood. Look it up—you’d have a heart of ice not to be moved by it.

I encourage you to read The Season. You’ll be warmed by the love of family and teammates and may even come to appreciate the role of Australian Rules football in shaping a young man.

Loved it!

You can reserve the paperback on the library catalogue or borrow the ebook and eaudiobook on Libby.

May 2025

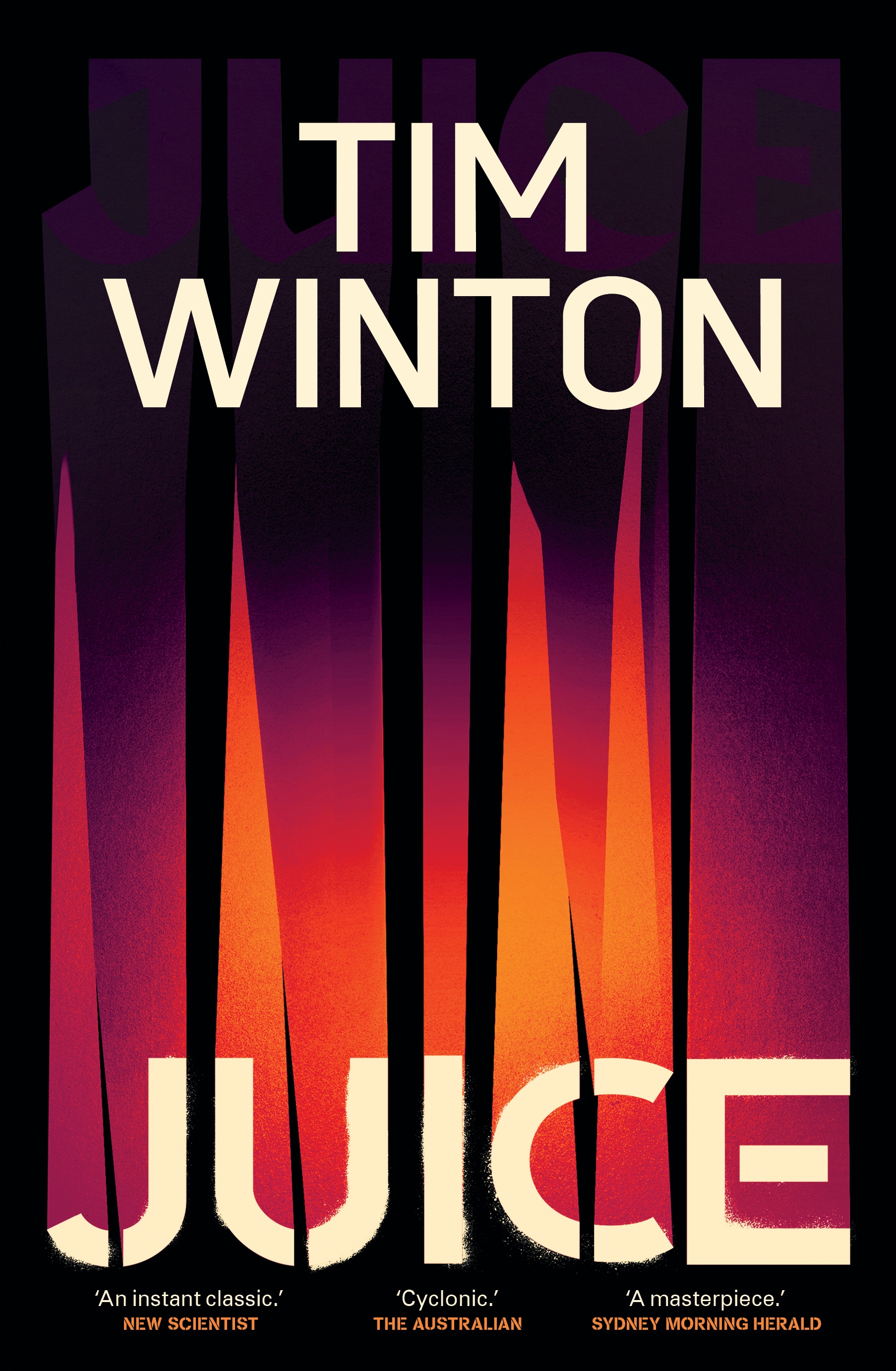

Juice

by Tim Winton

Juice is a huge book! Not only in its 500 pages but in its scope and the heft of its subject matter.

This is unlike any other Tim Winton book but it’s clearly reflective of the author’s deep concern about the natural environment and the future of his home state, Western Australia, in the face of climate change and our response to it.

The Juice of the title is fuel or energy but it’s also the juice of personal passion or determination and an antidote to the parched sunburnt landscape of a hot planet.

This novel is set in an unnamed future era and could be labeled speculative fiction. This landscape only allows people to live above ground in the winter months. In the extreme heat of summer where temperatures reach mid 50s, chores are done above ground between dawn and 10am or in the evening. Floods devastate and threaten lives and hailstones destroy anything above ground. Daytime hours in summer are spent in an underground ‘hab’. Water is collected or manufactured, solar and wind power runs pumps, fruits and vegetables are grown in sheds, diet is vegetarian and most animal life is extinct through heat or disease.

The main character in this novel is an unnamed plainsman homesteader who lives with his mother and makes his living through exchanging the food stuffs he grows and the items he scavenges from abandoned dwellings for the other materials he needs at the nearby hamlet market

Into this world comes vet assistant Sun, a city-raised young woman.

The novel opens with our protagonist narrator, and a young silent girl being accosted and taken hostage by the bowman, a stranger with a crossbow.

The bulk of the book is our narrator telling the story of how, unbeknown to his mother or Sun, he came to be recruited as a secret agent by the Service as a killer of those clan cartels responsible for climate collapse—the rich families and corporations who continue to live lives of opulence.

I had been forewarned that Juice is not an easy read and that it requires commitment. So I decided to devote several concentrated hours to really get into it without interruption. It worked. I read half the book in one afternoon and found it riveting.

The chapters are either the protagonist's linear past-tense narrative yarn, or present-tense chapters of the unfolding drama with the bowman, including the interchange of dialogue between the two.

This is a tragic story on a macro level and at the personal level of this man’s life.

It is also a deep dive into Tim Winton’s heartfelt concerns about the future of our warming planet, and the effects on his beloved home state.

I recommend that you approach Juice with the commitment of time to give this book sizeable chunks of your undivided attention. You will be rewarded.

You can reserve the paperback, large-print edition, the ebook, and the eaudiobook on the library catalogue.

April 2025

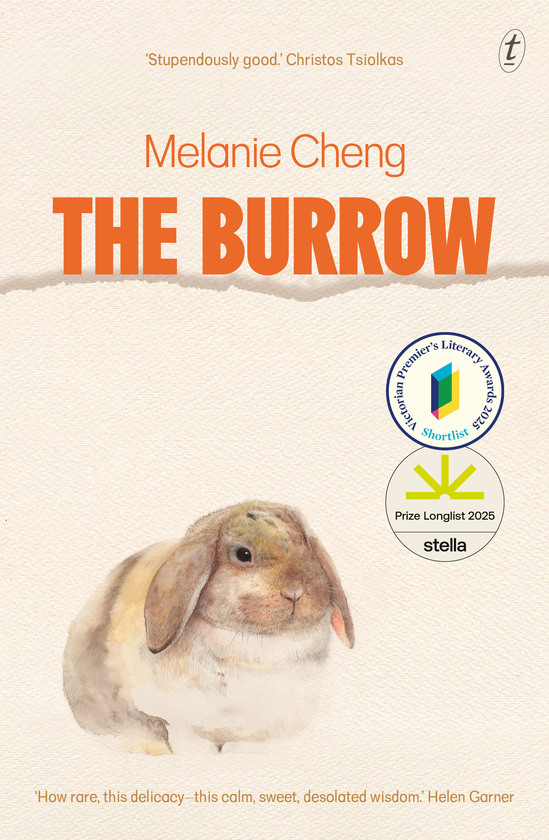

The Burrow

by Melanie Cheng

The words that spring to mind after finishing this short book are poignant and melancholic.

Helen Garner describes it as a ‘rare..delicacy… calm sweet desolated wisdom’ while Christos Tsiolkas writes that it is ‘surprisingly good’.

I read this book in a day and for much of it I had Judy Collins singing her hauntingly beautiful ballads in the background so the combination of the two brought tears to my eyes on several occasions. Accompanying music or not, this is a book that I guarantee will move you.

Married couple Jin and Amy, and their ten-year-old daughter, Lucie, live in inner-suburban Melbourne during COVID lockdown. On Lucie’s insistence, they purchase a pet rabbit. Then, Amy’s mother Pauline comes to stay after being hospitalised. This family has experienced a devastating loss, one that they do not talk about. They live individual lives of great grief.

There is tension in the unsaid. The three adults don’t like each other or themselves very much—or the other adults in their lives. They stop short of expressing blame, guilt, and secrets, and while they seem to be functioning on the surface, their daughter bears much of the load of grief as she tries to make sense of what has happened, and what is still happening. This is also a time of home schooling, so Lucie has no contact with her peers.

The short chapters in this book have very little dialogue but there is a richness in the third-person narrative from each of the four characters that exposes for the reader, their tensions, secrets, guilts, and despair—with occasional glimpses of positivity that allow us to think that there is hope for the future of this family. Interspersed between the Jin, Amy, Lucie, and Pauline headed chapters, there are a couple of rare short sections about ‘the rabbit’ written from his viewpoint too.

This rabbit—given the name Fiver—is also an isolated timid character, much like its human family.

The Burrow is a brilliant title for this book. Not only for its literal connection to the rabbit itself, but because it seems that each of the human characters has dug their own burrow to hide and protect their feelings.

The Burrow is Cheng’s third book. She is a Chinese Australian writer and a practising doctor in Melbourne. These cultural and professional experiences are reflected in this novel. Cheng also appears on ABC and SBS as a medical commentator. She won the 2018 Victorian Premiers Award for fiction.

This is a magnificent book that is a slow-paced gentle read that will resonate with everyone as it lays bare the pain of loss and finds a glimmer of hope that healing can occur.

I urge you to read it.

Available as a paperback, ebook, and eaudiobook on the library catalogue.

March 2025

Jamesby Percival Everett

While few Australians will have read Mark Twain’s great American novels The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and its sequel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, we are at least familiar with the basic story line.

In the better-know latter book, in 1861, Huckleberry (Huck) Finn, fakes his own death to run away from his alcoholic and abusive father. Jim, a slave owned by Huck’s guardian is also fleeing, having heard that he is to be sold and forced to leave his wife and daughter.

Together they undertake an epic raft journey down the Mississippi River to the dream of freedom in non-slavery states. Jim hopes that his freedom will allow him to return to liberate his family.

Some readers may also know that Twain’s original story is told in Huck’s first-person voice.

In this Everett novel, we hear the same storyline with the same encounters but this time, in Jim’s voice.

The first thing that struck me in the novel was the regular use of the horrific ‘N word’ by the white characters. This was also common in the original Huckleberry Finn novel and was uncomfortable for many readers when it was a school text in USA schools in the mid 20th century.

Using it in James is even more shocking today but it was important to be true to the era of the original. In fact it’s just one of the horrific racist reminders of the white supremacist view that was common.

What struck me next in this retelling, is the language used by Jim when speaking to whites. In chapter two, Jim is giving language lessons to his daughter and six other children. “White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them”, he tells them. Jim tutors the children to translate from the standard grammar they use between themselves, to the expected register “da mo’ betta dey feels, da mo’ safer we be”.

Jim can read and write but hides that from whites including Huck.

Last month, I wrote about The Reformatory, a novel exposing racism in the Southern USA States almost a century after this novel’s setting. There are sadly, so many attitudes that did not change in those 90 years. As we observe the present day USA, it seems there is still a long way to go. But we in Australia, can hardly hold a holier-than-thou attitude to race relations.

James is a magnificent read. It contains humour, horror, and hope. While entertaining, it is also deeply thought-provoking. Unlike Huck who enjoys the larks and escapades of an adventure down the river, James is constantly in fear for his life.

This book is rightly being acclaimed as the re-writing of the original, and giving James a three dimensional presence missing in the original.

If you have read the original, I’m sure this re-imagining will be extra meaningful for you, but if—like me—you haven’t read the Twain story, I can assure you that James is a full and rich experience that will engage you completely.

Thank you Percival Everett for providing non-Americans an insight into one of your classics, while teaching us that there is another perspective to the Hucklebery Finn canon.

Available as a paperback, large-print edition, ebook, and eaudiobook on the library catalogue.

February 2025

by Tananarive Due

This historical fiction is grounded in horrific times in Florida, USA.

The Gracetown School for Boys is a reformatory, a segregated prison farm for mostly young black boys, but also some poor white boys albeit in a different section of the compound. Yes, there’s some education involved, but mostly it is slave labour with ample doses of cruelty, and more.

This is Jim Crow America of the 1950s, where fierce segregation laws were in place (Jim Crow was an insulting name for Black Americans in that era).

The book is big. The story is big.

The Reformatory is about racism, humiliation, abuse, and murder.

The boys in this dreadful place are driven by the desperate need to simply survive.

Young Robert Stephens, aged 12, is sent to the Gracetown School for Boys as punishment for kicking a white son of a local wealthy landowner who made sexual advances to Robert’s 16-year-old sister, Gloria.

Author Tananarive Due is an educator and film historian with a special interest in Black horror. She has won numerous awards for her writing. At the start of the book, Due, lists the names of three family members including a great uncle, Robert Stephens, who died in Dozier school for boys in Florida in 1937.

While not biographical, there are elements of family history in this book.

Young Robert Stephens is an engaging protagonist with whom it is easy to empathise. From his swift kick to the knee of the boy harassing his loved sister, to his shame when he wets his pants in front of the school’s superintendent, Haddock—readers will relate. As his fear grows that his mishap will be discovered if a wet patch appears on the floor, we feel for him.

The book is also about competition and fear that is engendered between the boys, and about loyalty that develops in the face of shocking treatment. The dreaded ‘Funhouse’ and 'The Box’ are punishment rooms for the boys who break the rules or fail to inform on their peers.

During Robert’s time at the school, several other boys die and soon Robert is seeing these boys as haints around him. Robert has been raised with a fear of haints—the often-malevolent ghosts that conjure images and smells of past horrors. The haints of The Reformatory are not visible to most, but they drift around Robert with smells of burning flesh and images of brutality and bloody murder. These haints are often boys with horrific wounds and reflect that in the 1920s fire had claimed the lives of 30 inmates at this feared school. Haddock has strong motivations to expel these haints and enlists Robert as a haunt catcher.

Meanwhile, sister Gloria embarks on a crusade to set Robert free.

This is an epic novel. Although only set over a few months, it is broad in its scope, combining the story of Robert’s absent father, his dead mother, his brave and determined sister, and the broader society that facilitated racism, failed to question the cruelty, and ignored the evidence of abuse leading to death.

The Reformatory is almost 600 pages in length and has relatively few light moments, but it’s also an important read.

Young Robert is an example of many young black boys in mid century in the southern states of America. There are similarities to the stories from Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home that operated here in NSW from 1924 to 1970.

Robert’s story, like those of our country’s shameful stolen generations, should not be forgotten.

It was satisfying to note the reclaiming of ‘crow’ near the end of the book, as a term denoting survival and strength.

My only issue with this book is that it could have been a little more compact, but that’s a minor point.

Highly recommended.

2024 reviews

2023 reviews

2022 reviews

2021 reviews

2020 reviews

2019 reviews

2018 reviews